Climate

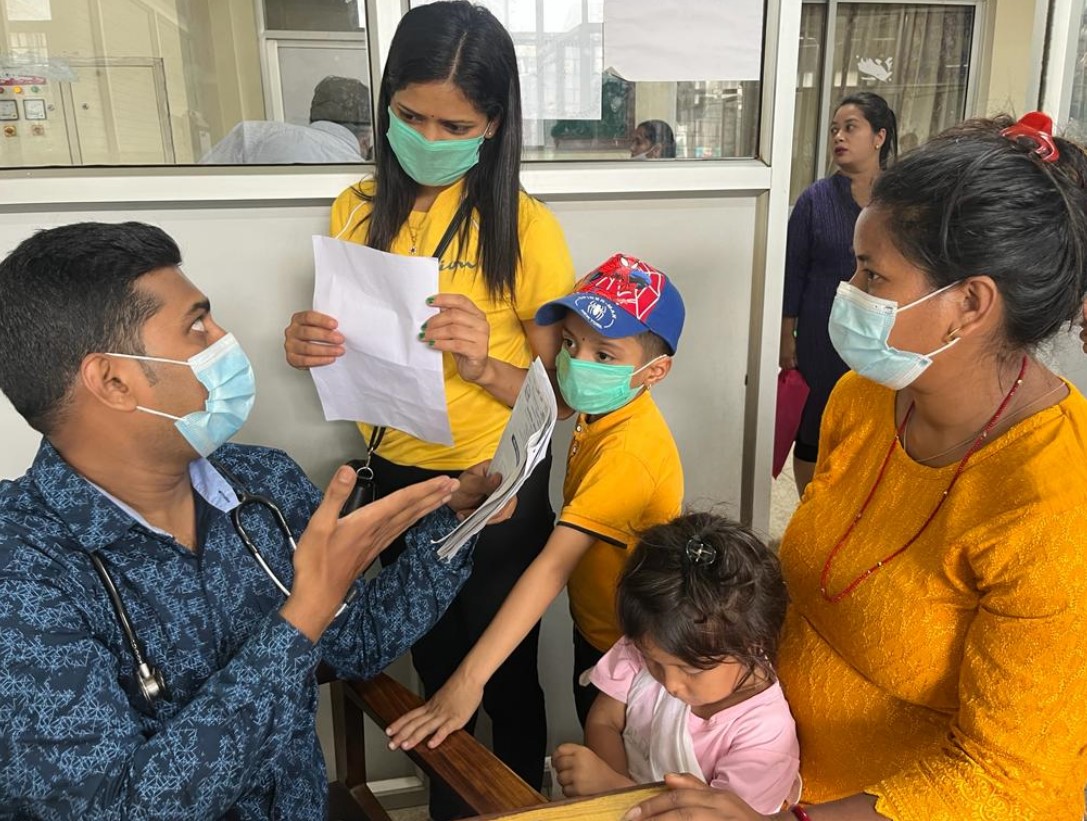

KANTI CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL, Kathmandu -

Three years old Pratigya Basnet holds on to her monkey doll even as her mother brings her into the doctor’s chamber for medical check-up. She carries it around her arms even when the doctor examines her.

“She was just beginning to recover from asthma, now she has a cough and a runny nose,” her mother, Pramila, tells the attending doctor, Shree Ram Shah. After a quick examination, he prescribes a nasal spray.

Then he calls the next patient: an infant boy, delicately wrapped around in his mother’s arms, brought for a follow-up check. Dr Shah remembers the patient with a slightly more serious-looking respiratory issue.

So he tells his mother: “He needs to undergo a bronchoscopy test.” It’s a procedure that enables doctors to look at the airways and the lungs through a thin, lighted tube. The mother will now need to go to another department in the hospital, where such tests are done.

Separate clinic

The pulmonory clinic is a new addition at Nepal’s oldest and most well-equipped children’s hospital - thanks to worsening air pollution in big cities like Kathmandu. It runs every Monday and Thursday, when it remains crowded with nearly 100 infants and children suffering from various respiratory diseases.

“Respiratory diseases is the biggest health problem we are handling these days,” says Dr Yuba Nidhi Basaula, the hospital’s director. “Now we have more children suffering from asthma, pneumonia and other respiratory illnesses. The disease burden wasn’t like this, say, ten or 15 years ago.”

Agreeing with many experts, he blames growing urban air pollution, fuelled by growing vehicular emissions, plastic burning and forest fires during winter and spring seasons, for the public health crisis. In rural areas, indoor air pollution remains a threat.

The urban air quality issue in the capital city appears more severe, though.

Kathmandu, the most-rapidly urbanising - and motorising - valley with a population of around 5 million remains most polluted. “Almost all the children who come here with respiratory illnesses are from Kathmandu [where air pollution levels are among the worst],” says Dr Shah at the clinic.

Equally affected are adults and senior citizens, who remain prone to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), one of the biggest killers, accounting for 20 per cent of all deaths after cardiovascular diseases, according to the Nepal Burden of Disease 2019 report by the Nepal Health Research Council.

No wonder an international study released in August 2022 ranked Nepal as a country with “the world’s highest age-adjusted death rate for chronic lung disease at 182.5 per 100,000 population, with more than 3,000 years lost to ill health or disability from the condition”.

“All cases of COPD are environmental in origin”, according to an author of the study, Jay Kaufman, also a professor at MicGill University, Montréal, Canada.

How bad is pollution?

Growing international concerns over the country’s constantly deteriorating air quality in recent years prompted the government to set up 26 air quality monitoring stations in major urban centres.

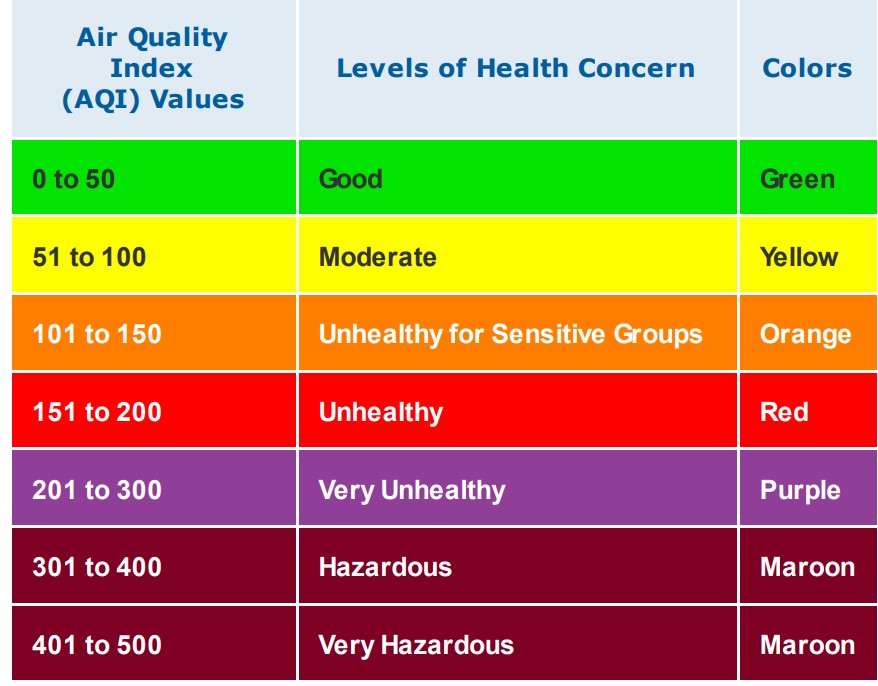

Often, the Air Quality Index (AQI) data fed by the stations paint a grim picture, with air quality failing to improve even during the monsoon season. In winter and spring, the air quality sharply deteriorates, reaching hazardous levels, with the AQI crossing 300 mark.

After all, winter is that time of the year when plastic burning and forest fires become commonplace nationwide.

Even during monsoon - at the time of writing this - at least one station, at Sankha Park near the Ring Road in Kathmandu, has been feeding an AQI of 60. That, according to the World Health Organization, is “not good” for human health. It recommends AQI of 50 or less as safe.

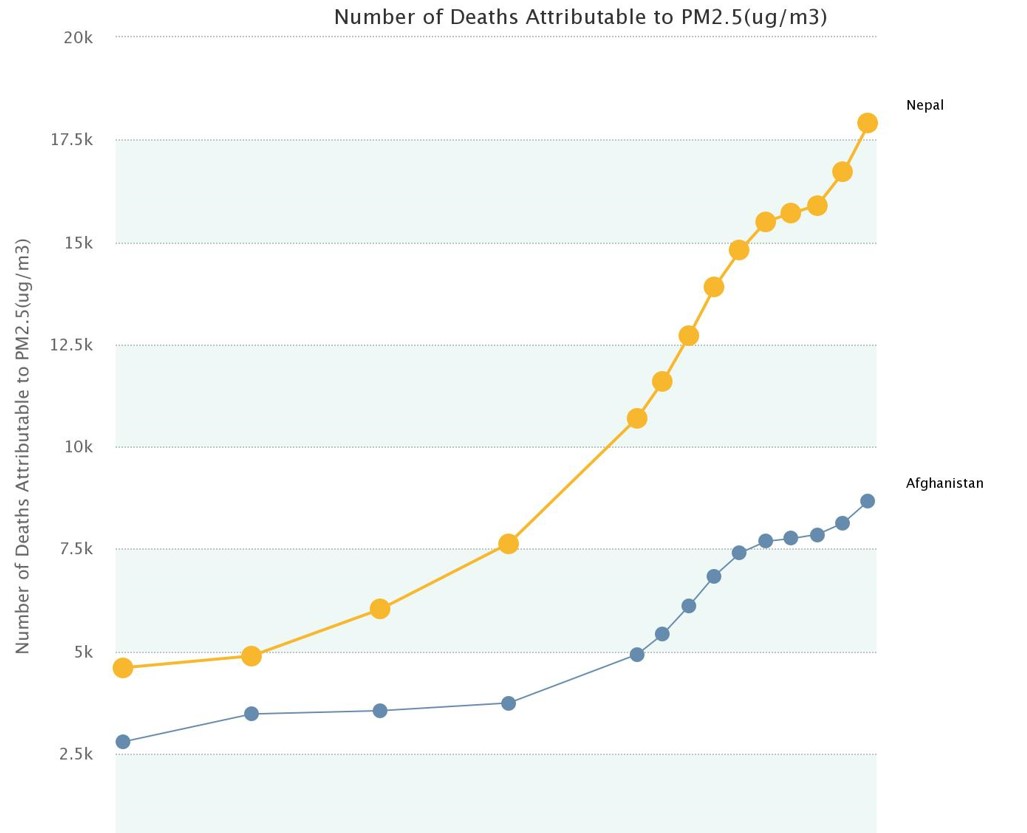

That’s precisely why major international studies, including the State of Global Air report 2020, have placed Nepal among the most polluted countries in the world. In 2019, the report said, the country recorded the highest outdoor PM2.5 levels and an annual average emission of 83.1 micrograms per cubic meter of PM2.5. (See a chart on deaths from the report).

PM2.5, often found in smoke and air, are very tiny particles, with a diameter of 2.5 micrometres, or 0.0025mm, or even tinier. They can easily enter human lungs and bloodstream, posing serious health risks from toxic gases such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide, which are found in diesel and coal fuel exhausts.

“If they are not wearing a good mask, children [or adults] always remain at risk of getting affected [by such toxic particles],” says Dr Basaula, the children’s hospital director.

The health risks from long-term exposure to PM2.5 include: ischemic heart disease, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory infections, stroke, and deaths of new-born babies, besides other health complications.

The impacts are already there and supported by evidence.

Alarmingly, the State of Global Air report 2020 said, PM2.5 pollution claimed the lives of 17,900 people in 2019, with overall air pollution causing 42,100 deaths in the country that year.

Fossil fuels’ impacts

Although indoor air pollution, mostly caused by firewood or dung, has been found to be the biggest spoiler in rural areas, vehicular emissions stemming from Nepal’s ever-growing fleet of fossil fuel-run automobiles have been found to be “the major polluter”.

Several past studies have pointed at vehicular emissions and re-suspended dust as the primary source of particulate matters. And vehicular emissions alone account for more than 31 per cent of the air pollution in Kathmandu, according to a 2017 research Shakya et al cited by a recent Japanese-led study.

Other contributors included soil dust (26 per cent), biomass and garbage burning (23 per cent) and coal-powered brick kilns (15 per cent).

At COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, Nepal’s prime minister pledged net-zero by 2045, and increasing the sales of private electric vehicles by 90 per cent by 2030 – although sales of electric public transport by only 60 per cent by 2030.

Despite making such climate action promises, including fully switching to electric vehicles by 2031, Nepal continues to import tens of thousands of smoke-belching automobiles every year.

In all, their numbers hover around 3.1 million nationwide, according to the Department of Transport Management. And nearly 80 per cent of them are two-wheelers, half of which run on the streets of Kathmandu valley, emitting fumes.

Less than one per cent of them are electric-powered.

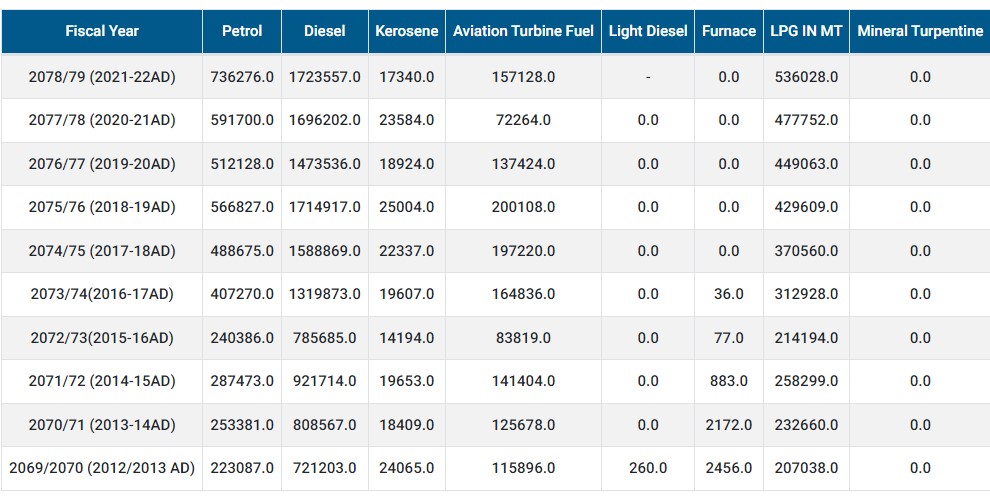

Sales of private electric vehicles have started going up in recent years. And a few dozen electric buses for public transport have been introduced. Yet the country continues to rely heavily on fossil fuels such as petrol, diesel, liquefied petroleum (LP) gas, kerosene and aviation fuel to run automobiles, kitchen stoves and aircraft.

Separately, the brick and other industries continue to import coals to run their kilns – another source of PM2.5.

In a country with immense hydropower potential – but often-hazardous air quality - what’s worrying medics and environmentalists is Nepal’s growing reliance on fossil fuels (See Nepal Oil Corporation's sales chart below). Equally worrying, they say, are the new plans to build at least three more petroleum pipelines connecting towns across the Nepal-India border.

Last fiscal, petroleum imports accounted for over 17 per cent of the country’s total imports, followed by fossil fuels-run automobiles and spare parts that accounted for 6.5 per cent, according to the Department of Customs.

It says the country’s fossil fuels imports shot up by almost 80 per cent in the last fiscal compared to 2020-2021. And 60 per cent of the imported fossil fuel was diesel, considered to be the biggest source of PM2.5.

Solution to pollution

Against such a backdrop, one wonders what the government should do to reduce fossil fuels’ adverse negative impacts on public health and environment.

Bhushan Tuladhar, an environment expert and a board member of Sajha Yatayat which, in 2022, introduced 40 electric buses for public transport in Kathmandu, suggests that there’s no option but to go for cleaner options.

In 1975, he notes, Nepal had shown the way by successfully operating electric buses along the Kathmandu-Bhaktapur route, and in 1995, Safa Tempos, the electric three-wheelers, were introduced on the streets of Kathmandu.

His suggestions include: further promoting improved cooking stoves for rural households; switching to electric vehicles for private and public transport in Kathmandu and other cities; developing electric metro trains and railways; introducing electric freight trucks; and promoting renewables such as solar and wind power for industrial uses.

“We have surplus hydropower now, we can use that to power our electric vehicles,” he says. “Now we should invest in electrification of the entire fleet of vehicles used for public transport. That way we can dramatically reduce vehicular emissions.”

Once Nepal succeeds in significantly reducing the continuing large-scale diesel-burning, it can easily win in its battle against air pollution, Tuladhar adds.

Equally important, he says: “We have older models of diesel-run vehicles, which cause more pollution. Now it’s high time Nepal, like India, introduced only the Euro 6 vehicles, with better emission standards.”

Madhu Marasini, the secretary at the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies, also the chairman of Nepal Oil Corporation, says the government’s “standing policy” is to reduce consumption of fossil fuels and harness clean energy.

With more under-construction hydroelectric plants coming on line, Nepal has started generating almost-enough electricity for domestic consumption. During monsoon, when the production remains higher, it has even started exporting surplus power to India.

By 2024, the country is expected to generate 4,500 megawatts, with plenty of surplus to export, or use to run electric vehicles and even trains.

“We are already promoting electric vehicles,” he says. “To find long-term energy solutions, we have initiated research, including on the possibility of producing green hydrogen.”

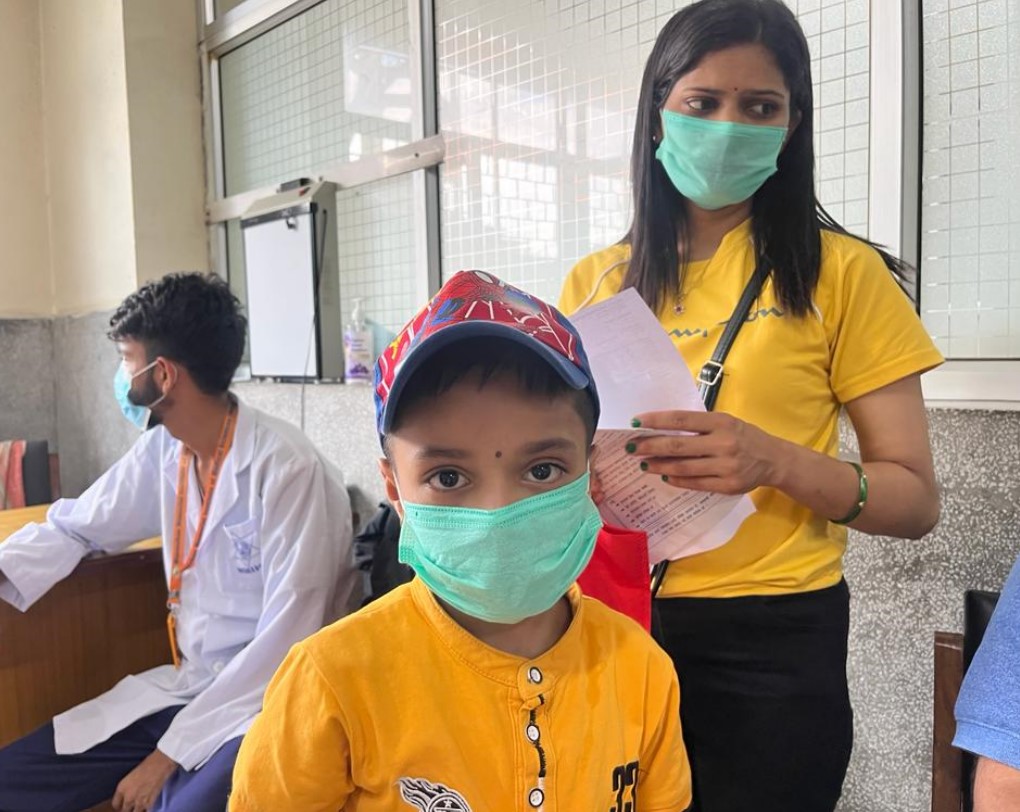

The masked-up child

Until that happens, says Dr Basaula, the director at the children’s hospital, “we have no choice but to wear masks every time we have to go out.” Even more so in the case of infants and children, he adds.

To those of the little ones already suffering from respiratory issues like asthma, doctors generally prescribe inhalers such as Asthalin and Foracort. For complicated cases, they prescribe antibiotics.

One such asthma patient is eight years old Elson Adhikari, accompanied by his mother, Sunita. The resident of Balaju says her son started taking inhalers since he was three years old as soon as he had been diagnosed with asthma.

No wonder Elson now knows the correct spellings of the inhalers. Asthalin is easy to spell.

“But Foracort?”

“Foracort is spelt F-O-R-A-C-O-R-T,” he interrupts in a loud and clear voice, when I try to double check the spelling with his doctor. Turning around, I looked at his face to see how he spelled the letters.

He was masked-up, his nose and mouth safely covered.

"He has been wearing mask like this since he was three," his mother adds.

Also read: KMC's tobacco ban goes up in smoke

Also read: Vaping businesses boom in Nepal

Also read: Air pollution killing thousands in Nepal every year